Review by Kristen Brida

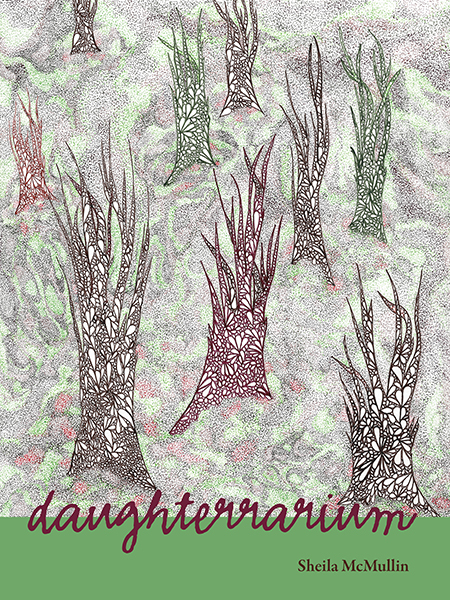

daughterrarium

Cleveland State University Poetry Center

Author: Sheila McMullin

978-0-9963167-5-0

4/1/2017

$ 16.00

I have read through McMullin’s debut collection daughterrarium at least twice. The first time I read them, I scribbled in the margins with a little more urgency than when I take notes for other books I read. The second time I read this book, I wanted to wade through these poems, and experience habitats these poems construct. And yet, within the first ten I found myself once again grabbing for my pen and writing whatever I could. To be completely honest, the poems in daughterrarium speak to the experience of a feminine body in a masculine-dominated society in an unrelenting, a connective fashion.

The poems in this collection weave in and out of restraint and unleashing, direction and veering. In the first poem of the book, “Tapering,” the speaker jarringly detaches pronouns from the rest of the poem. McMullin writes:

(I) looked out the window, no

like killing myself had never come

into my own before, no

My tongue dried with half the pill.

The speaker here reveals in the most direct way and uses clear and specific detail. And yet this near-erasure of the “I” in this poem complicates this frankness. We are left to question the role of this shelled and/or ghostly “I” both present and not present in the end of the first poem.

The directness does show throughout daughterrarium, but it is most tugging as we further read the collection. McMullin sprinkles throughout short italicized poems floating without titles. These fragments are striking, subtly confronting how women relate to their bodies in a patriarchal world. The speaker asks us:

Do you fear

Or have feared

your body

because you love

your body and your

entire life were shamed for being so loving?

Because loving means you feel comfortable alone

and no one has ever left your body alone

These line breaks cut off in a way that oscillates between a delicate and heavy delivery. Although a direct address, the speaker angles her perspective in a way that cuts through in such a brutal exactness. The speaker here argues the discomfort of the feminine body as a condition of the patriarchal terrarium, rather than an innate condition of feminine body.

McMullin also writes of the sexualized body as both a site of trauma and violence, and a turning point in the mother-daughter relationship. In “Act IV: Knot Who” of the titular poem of this collection, the speaker reveals the violence of entering womanhood. The speaker talks of a daughter’s first period, detailing the discomfort of this entry, detailing it, “Felt like wet sand caught in the crotch of her bathing suit when she was younger and at the beach. Chunky and gooey and rose is a rose is a rose is rose-colored.” This borrowing from Stein, turning rose from noun to adjective is an abstraction that feels eerily similar to the kind of treatment of feminine bodies. The self attached to the feminine body preceded by their ascribed adjectives, a description overriding the noun itself.

The poem turns with the mother entering the poem. The mother tells the daughter:

Yes, you could have babies now. But don’t until you have a good job. You’re doing a good job now. You did the right thing telling me. Mark the phase of the moon on your calendar. Vitamin C can help if you bleed too heavy. It will be good to remember that.

As I read the last two sentences of the poem, I am especially reminded of a Greek scholar (I forget which one) who said women’s bodies are grotesque sites because their menstruations blur the boundaries between self and other. At first, I read this prescription as something to plug this boundary to assuage this fear, revealing some sort of power dynamic of the female body in a patriarchal society. However, after doing my own research, I realized the mother’s suggestion is a way for the daughter to take care of her own body. The sterile syntax and somewhat detached nature coupled with the kind gesture shelled within it, I think says a lot about how we approach the discourse about caring for a feminine body. It is approached carefully, but without involving “too much” of the personal experience. It creates this hint at a desire for connection, and yet somehow, a restraint.

There is so much more to discuss and write about daughterrarium, but I don’t want to spoil the experience of reading this book. McMullin focuses and reveals the many ways the feminine body is exploited, is overpowered in the patriarchal schema of the world. She reveals these dynamics in ways that play with the reader, then confront the reader, and finally blossoms within the reader. Simply put, daughterrarium is one of those collections that allows you to revisit the poems and feeling as if it is the first time you have read these poems.

Sheila McMullin is author of daughterrarium, winner of the 2017 Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Prize chosen by Daniel Borzutzky. She co-edited the collections Humans of Ballou and The Day Tajon Got Shot from Shout Mouse Press. She volunteers at her local animal rescue, is a youth ally and organizer, and holds an M.F.A. from George Mason University. Find more about her writing, editing, and activism online at www.moonspitpoetry.com.

Sheila McMullin is author of daughterrarium, winner of the 2017 Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Prize chosen by Daniel Borzutzky. She co-edited the collections Humans of Ballou and The Day Tajon Got Shot from Shout Mouse Press. She volunteers at her local animal rescue, is a youth ally and organizer, and holds an M.F.A. from George Mason University. Find more about her writing, editing, and activism online at www.moonspitpoetry.com.

Kristen Brida’s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in New Delta Review, Bone Bouquet, Hobart, Barrelhouse,

Kristen Brida’s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in New Delta Review, Bone Bouquet, Hobart, Barrelhouse,

Whiskey Island, and Tinderbox.

She serves as the Editor in Chief of So to Speak and is an MFA candidate at George Mason University. She tweets @kristenbrida.