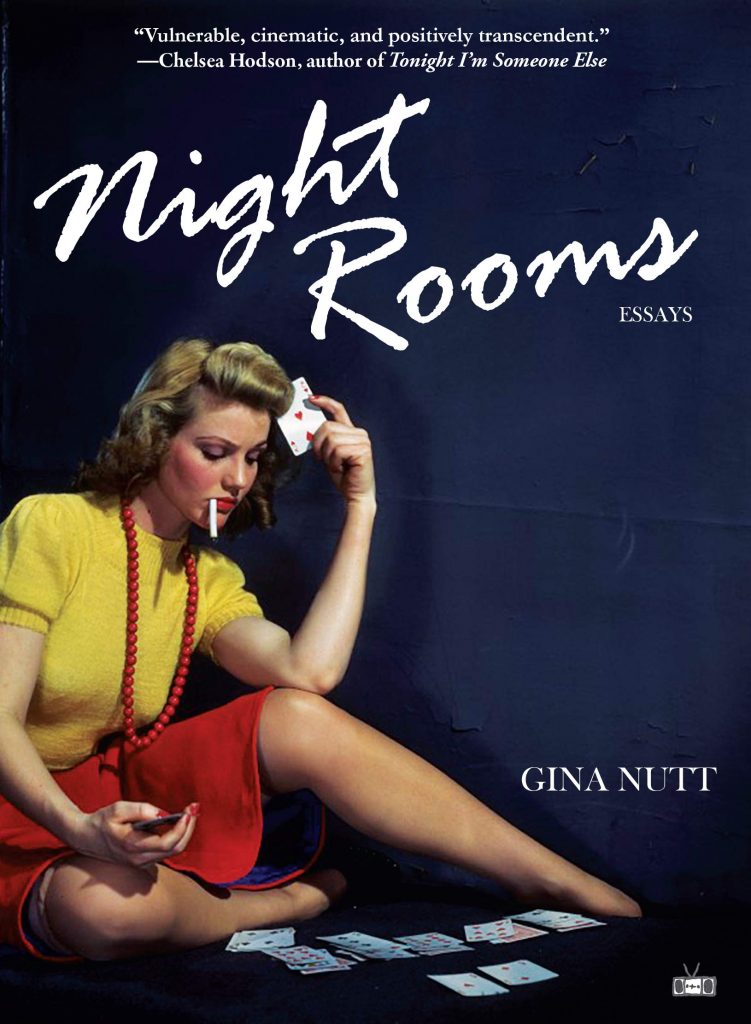

Reading Night Rooms transported me to the dim orange light of my childhood bedroom. At fifteen, I spent my nights poring over The Rough Guide to Cult Movies—its sections labelled Euro Horror and The Devil—circling titles, planning my next trip to the video store. As I read Gina Nutt’s atmospheric, structurally inventive essays, I remembered seeing movies like Suspiria and Rosemary’s Baby for the first time, the recognition and bewilderment that followed.

The structure of Night Rooms echoes the way we often watch and remember horror films. Clips, a series of striking moments. Small, unsettling details that stay with us.

Nutt uses movies as a lens to examine the horror in the everyday—in a homebuyer’s class, a beach vacation, bridges, and suburban malls. And though Night Rooms meditates on dark subjects like suicide, grief, and mental illness, the book never feels morbid or hopeless. In fact, Nutt’s treatment of these subjects is at once compassionate and incisive; her willingness to talk about the things we, as a culture, don’t talk about feels revelatory.

Night Rooms is meditative and circular. While Nutt separates each essay into numbered sections, the chapters bleed together; images refract and repeat. Night Rooms works best when considered as a full work, a book-length essay, rather than a collection of essays with neat beginnings and endings. The title aptly captures my reading experience—almost like drifting from room to room in a haunted house. Each room is connected, but beholds something different: white deer, taxidermy tableaux, beauty pageants, the ocean, a horror movie playing on loop in a college apartment. Night Rooms transports the reader into each scene, moment, and feeling with visceral, striking language.

However, Night Rooms occasionally sacrifices clarity for lyricism and elegance in its language. While I found myself getting lost in Nutt’s hypnotic prose, stylistic choices sometimes pulled me out of the reading experience. Some films are referenced in the notes of each essay, while some are only referred to in description. I often found myself dying to know what Nutt was referencing, wanting to add another movie to my watchlist. There were also moments when I found myself wanting just a bit more context to understand the author’s experiences. Though Nutt examines the power of the unsaid, of absence, a lack of context was occasionally distracting.

That being said, what Nutt doesn’t say is often just as powerful as what she does say. In section 8, Nutt meditates on a number of ideas—survival, sexual assault, revenge, and trauma, to name a few—and cites films such as The Last House on the Left, Teeth, and Carrie. Nutt examines the infamous rape scene from The Last House on the Left; a former boyfriend of hers insists it’s necessary to see the assault to understand the parents’ need for revenge. In this essay, Nutt masterfully reflects on the “final girl” trope, connecting it to her own experience of sexual assault and the reality of telling one’s story:

“I’ve heard Speak up said in a scolding way, sharpness in encouragement, edges like Spit it out. […] Like the language for everything that has ever happened exists. Any saying feels like he and I were, are, both on trial.” (68 – 69)

“One assumption about a final girl being the person who lives to tell the story is that her survival is attached to telling; she is expected to say it, to tell, again and again; she can’t live without a saying so revealing she is bare before the audience, the moment is bare.” (69)

In defiance of horror movies that so often exploit women characters, Nutt withholds details of her own experiences. In this section, Nutt has made a conscious choice to create boundaries with the reader. While Nutt explores her own morbid curiosity, she refuses to indulge ours—she does not give details about an experience of sexual assault, nor about the suicides she describes. Her refusal to give the reader everything challenges our expectations, forcing us to reflect on why we want writers of nonfiction and other confessional genres to reveal every last detail.

Gina Nutt has a knack for describing unexplainable experiences and feelings, not so much analyzing, but shining a flashlight in their direction. Throughout the book, Nutt references “The Four-Day Win”, a terrifying, unidentifiable presence she felt during childhood. Nutt doesn’t remember what she saw, but suspects it was “something I felt, a phrase for a heavy feeling” (45). Nutt’s childhood self did not have the language for what she was experiencing, her words a “mangled strangeness” (95).

Night Rooms may not leave the reader with sharp, clear conclusions. Nutt meditates on so many subjects that the book can seem wandering or distracted at times. But Night Rooms is carefully woven, and by the end, each idea feels deeply and intrinsically connected. I was left with a distinct, but enigmatic, feeling. The book washed over me, each essay a wave in a massive ocean (which, for Gina Nutt, represents a fear of the void; the unknown.) When I finished Night Rooms, I felt inspired to experiment with language more, to look at the world closely, and to watch more horror movies. And then I returned to the beginning and read it again.

Buy Night Rooms from Two Dollar Radio, $15.99.

S.J. Buckley is originally from Slower Lower Delaware. She earned her MFA in creative nonfiction from George Mason University, where she was the Nonfiction Thesis Fellow. She also served as the Nonfiction Editor of So to Speak journal for two years. Her writing has appeared in Ligeia, Grub Street, and the So to Speak blog.