I, like many people, was raised on fairytales—specifically, the Western fairytales that dominated my elementary education. By the time I reached kindergarten, I was among the throngs of small children who could recite “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Rumplestiltskin,” and “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” from memory. More significantly, I was well-versed in the world of Disney Princesses and their softened, distorted versions of fairytales. A bookworm from birth, I identified strongly with Belle from Disney’s take on Villenueve’s “Beauty and the Beast,” adopting her “nose stuck in a book” attitude from earlier than I can even remember.

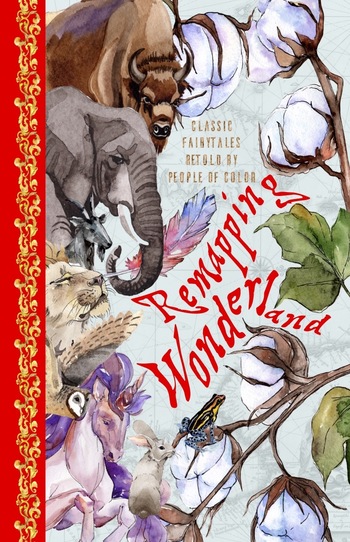

Remapping Wonderland is not a set of Disney fairytales. It is not, for that matter, Hans Christian Andersen or the Brothers Grimm, either. It challenges the canon, rather than adhering to it; it is something entirely new, freshly exploring stories well-known across the world. For starters, the collection is written entirely by BIPOC writers, platforming creators who have traditionally been excluded from the white, Western literary canon; as a result, the re-imaginings are authentically, culturally diverse. Take, for example, Eneida Alcalde’s “The Empanada Man,” which uses the story of “The Gingerbread Man” to tell a tale of Mexican immigration and capture at the border. Originally an American story emphasizing the importance of being careful about trust, Alcalde shifts the cultural frame of the story to a commentary on the cruelty of American immigration practices, particularly along the Mexican Border. In contrast, Wen Wen Yang’s “The Fox Spirit,” originally published by our very own So to Speak, reimagines a fairytale within its own Chinese cultural origins, centering the would-be antagonist as the narrator to complicate ideas of good and evil. The collection is full of these turns, often moving between them from each story to the next.

One of my favorite stories in the collection, “Dara and Noori” by Jayet Moon, creates a fantastical alternative history centered on a royal family and civil war in 17th century India’s Mughal Empire within a reimagined narrative of Villenueve’s “Beauty and the Beast.” The protagonist, Noori, is an outcast because her godmother, Jahanara—the daughter of the emperor and the woman for whom the Taj Mahal was built—provided her with a Muslim name, even though she would be raised Hindu. Noori grows up to be smart and beautiful and captures the attention of Prince Dara Shikoh. Soon, though, Dara’s evil sister, Roshanara, kills their father and Dara. A witch, Roshanara requires a vial that their sister, Jahanara, gave Noori as a baby that contains their late mother’s tears in order to finish her evil plan. Knowing this, Noori flees to another town and seeks shelter in a black Taj Mahal with a beast.

The rest of the story makes use of recognizable elements from Villenueve’s “Beauty and the Beast;” however, including reimagined history for the Mughal empire twists the tale and defies canonical expectations. What I love so much about this story is the way it plays with the expectations of both the tale of “Beauty and the Beast” and of the Mughal empire, creating a story all its own. It challenges the canonical Western fairytale, which often requires a single hero or heroine, and instead formulates a story which is resolved by collective determination. The story of “Beauty and the Beast” is enriched by the threads of religion, Mughal and Indian culture, and collective philosophy. It was after reading this story that I had to put the book down for the day to ruminate in how incredible it was, and it’s stuck with me since.

The ability to read this book in chunks, due to its being a sequence of short pieces, is another selling point in an ever-busy world. The short, individual stories told in this anthology made it so easy to sit down for just twenty pages between tasks. I came to look forward to this part of my day, when I could sit down to previous So to Speak contributor Christiana McClain’s retelling of “The Creation Myth,” Torie Comeux Plowden’s reimagined “Twelve Dancing Princesses,” or Mina Li’s reinterpretation of “The Little Mermaid,” one at a time. It gave me the opportunity to rethink stories I grew up hearing and allowed me to complicate my own notions of what fairytales are and can be. Put together, this anthology is page after page of complicating, challenging, and reimagining stories to shape the genre into a greater representation of our world.

You can find Remapping Wonderland: Classic Fairytales Retold by People of Color here.

Amanda Ganus is originally from Lubbock, Texas. She is an MFA student in Creative Nonfiction at George Mason University and is the Assistant Editor-in-Chief of So to Speak. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Dunes Review, The Nasiona, and The Plentitudes.