As I pondered a pronoun change, I began to think of gender less as a scale and more as a landscape. Some people are born in the mountains, while others are born by the sea. Some people are happy to live in the place they were born, while others must make a journey to reach the climate in which they can flourish and grow. Between the ocean and the mountains is a wild forest. That is where I want to make my home (191).

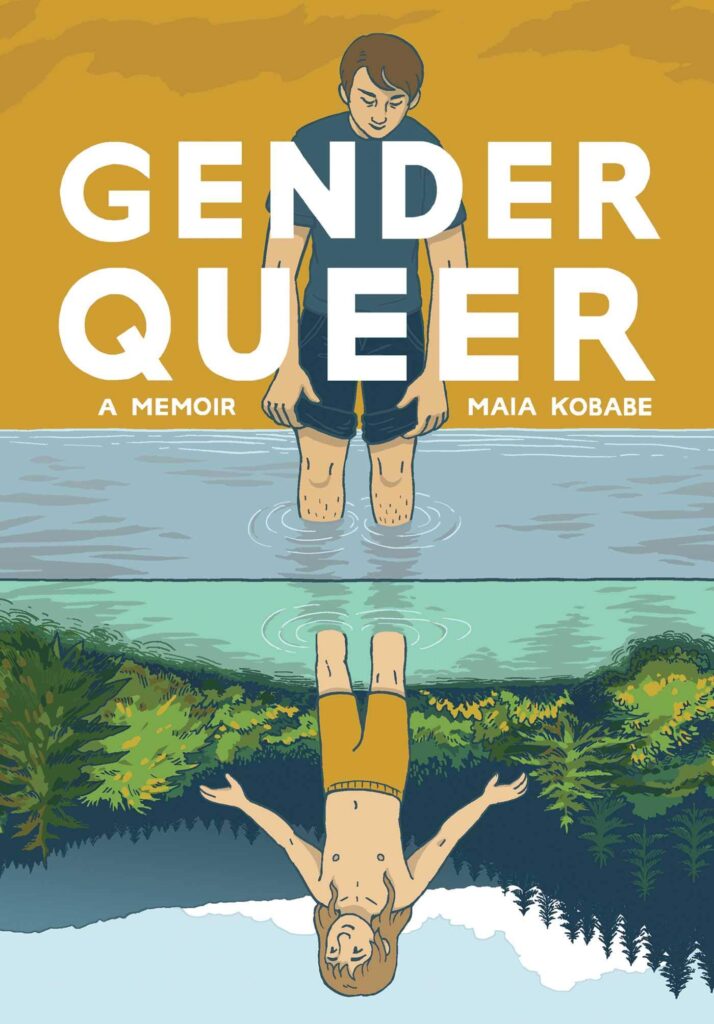

I wish I had read this quote from Maia Kobabe’s graphic memoir Gender Queer prior to when my mom asked me how she should think of the students in her class who use non-binary pronouns. She teaches at a Title I middle school in Raleigh, North Carolina, meaning many of her students are not only experiencing shifts in gender identity but also shifts in their living situations or access to meals due to financial instability. In other words, identity is just one of many crises her students face every day. My mom seems to have grasped and accepted the concept of transgender identities quite well, but non-binary identities continue to baffle her. She seems to forget that forests exist, assuming instead that all beaches must slope directly into rocky peaks, allowing nothing to grow in between. In reality, gender identity is so much hazier, something that Maia Kobabe (e/em/eir) demonstrates with raw honesty in eir graphic memoir published in 2019.

In Gender Queer, Kobabe describes eir lifelong body dysphoria regarding eir breasts and genitals and explains how that feeling of disconnect with eir body and with female gender roles more broadly helped steer em toward acceptance of a non-binary identity. In addition to questioning eir gender identity throughout the memoir, Kobabe also interrogates eir sexuality and describes various instances of sexual experimentation, leading to the realization that sex is not something e desires. This aspect of the graphic memoir is what drew me into the narrative. As an asexual woman who isn’t sure how to come out to her family, I was eager to learn how Kobabe came to navigate eir sexuality and share eir identity with eir parents.

Throughout most of Gender Queer, Kobabe seems rather fortunate to have a supportive social circle that includes several other LGBTQ+ persons of varying identities. However, Kobabe’s book does not depict a queer person’s coming out fantasy, as there are still challenges e must overcome in explaining eir identity to eir parents and relatives and in combating eir own hesitation to speak up for the use of eir pronouns. Following Kobabe’s acceptance of eir non-binary identity and request that relatives use e/em/eir pronouns, e was subject to several harsh and ignorant comments, including “Why are you doing this to us?” and “Your happiness is very important to me. But I have a hard time seeing this trend of FTM trans and genderqueer young people as something other than a kind of misogyny. A deeply internalized hatred of women” (195).

Stories like these are the reason I continuously encourage my mom to use her students’ pronouns, to be discreet and not out them to their parents, and to understand that, just because an AFAB student wears a skirt, it doesn’t mean the he/him pronouns are just a phase (my mom is trying to learn; she really is). Gender is so much more flexible and far-reaching than the roles to which society has attempted to confine it, and my mom’s students are already demonstrating immense courage by advocating for themselves and requesting their pronouns at such a young age. However, despite my advocacy for queer awareness and acceptance, I still can’t seem to be honest about my own identity as an asexual woman with my mother.

Assumptions such as the ones Kobabe faced in eir own life and the ones my mom still fleetingly succumbs to on occasion are why a graphic memoir published in 2019 is still worth writing about and discussing today. In fact, in my home state of North Carolina, the discussion surrounding Gender Queer became rather heated over the winter holidays, as the Wake County Public Library system banned the book following a complaint submitted to the county’s Library Director and Deputy Library Director on December 13, 2021. The complaint, written by a local library patron, claimed that Gender Queer was pornographic and asserted that taxpayer dollars should not contribute to purchasing library copies of the book. Admittedly, the graphic memoir does contain illustrated sex scenes, full-frontal nudity, and the use of sex toys, but the inclusion of such scenes contributes significantly to the narrative of self-discovery rather than exist solely for the purposes of erotic stimulation. Moreover, the Wake County Public Library system has not banned other sexually explicit books, such as Fifty Shades of Grey and graphic novel series Saga, leading many Wake County librarians and library patrons to wonder if Gender Queer’s exclusively LGBTQ+ sex scenes were the true cause for the ban.

Many Wake County librarians protested the initial ban of Gender Queer, and 50 of them signed an open letter claiming that the ban contradicted the code of ethics instituted by the American Library Association. The code of ethics includes, among others, such principles as:

We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources.

We do not advance private interests at the expense of library users, colleagues, or our employing institutions.

We distinguish between our personal convictions and professional duties and do not allow our personal beliefs to interfere

with fair representation of the aims of our institutions or the provision of access to their information resources.

In addition to concern over a potential violation of the code of ethics, Wake County librarians have reported that they’ve been permitted little involvement in the collections development process and that they have perceived their work environment as “vindictive” toward librarians who complain about book selections or removals. Following the open letter signed by Wake County librarians, library administrators promised to develop a more transparent policy for removing books. For now, Gender Queer has returned to the shelves of Wake County libraries, but once the new policy is approved, its content will be reevaluated, allowing the potential for another ban.

Unfortunately, efforts to ban books have reached their highest frequency since the 1980s. Oklahoma’s State Senate proposed a bill that would prohibit libraries from acquiring books that explore sex, sexual identity, or gender identity; McMinn County Board of Education in Tennessee removed graphic novel Maus, which won the Pulitzer Prize for its stark and unflinching depictions of the Holocaust and concentration camps, from its eighth grade curriculum; and Governor of Virginia (the state in which I attend graduate school) Glenn Youngkin argued that book bans are an important aspect of parental control, citing Toni Morrison’s Beloved as a text potentially worth removing from schools.

This list of book bans and ban proposals goes on and on, and the accessibility of certain content in schools and public libraries is no longer a concern solely among individual parents. Entire organizations have been founded with the purpose of proposing books that should be banned and organizing lists of “dangerous” texts that parents can share on social media, even if they’ve never read the books themselves. No Left Turn in Education is one such organization, which categorizes the books it insists should be banned into three categories: Critical Race Theory, Anti-Police, and Comprehensive Sexuality Education. In other words, children shouldn’t be able to read any texts that describe the plight of enslaved persons, analyze power structures based on race, expose instances of police brutality, portray LGBTQ+ identities or relationships, or contain honest and straight-forward discussions of consent. No Left Turn in Education claims that books in these categories should be banned on the basis that they “spread radical and racist ideologies to students,” and “They demean our nation and its heroes, revise our history, and divide us as a people for the purpose of indoctrinating kids to a dangerous ideology.” What No Left Turn in Education doesn’t realize is that silencing its blacklisted authors will not bring this nation unity. Ignoring the differences in privilege and opportunity that exist in our society does not mean those differences don’t exist. If anything, pretending our nation lives in complete harmony only means more problems and inequalities will accrue and will be swept under the rug due to a lack of awareness.

I wish I could say that a revision of Wake County’s policy for removing books gives me confidence that Gender Queer will remain on my local library’s shelves, but it doesn’t. Not in North Carolina, where sex ed teachers are only permitted one school day to explain the complicated concept of (exclusively heterosexual) intercourse to students, where HB2 was written into legislation, and where the state’s Lieutenant Governor told a church congregation in October, “There is no reason anybody, anywhere in America should be telling a child about transgenderism, homosexuality, or any of that filth.”

Even the initial complaint sent to library administrators about Gender Queer seems to echo Lieutenant Governor Robinson’s prejudices and reveal the baseless “justifications” for banning books in Wake County. Under the Request for Reconsideration form’s prompt, “Please state how reading this book might affect the reader,” the complainant responds, “When I was 13 y/o, I desperately wanted to be a boy. Thankfully, the transgender movement was unheard of, or I might have jumped on board. If I had read this book at the time, I might have been encouraged to seek medical intervention to become a boy. Thank God that wasn’t a choice then!” Yeah, thank God you didn’t have the freedom to explore your identity thoroughly. Could you imagine the consequences? Much better to submit ourselves to society’s restrictions. In fact, I wish I still didn’t have the right to vote; far too many options on those ballots.

The complainant worries that young adults may be inclined to pursue drastic changes after reading Gender Queer, but it’s worth mentioning that Kobabe doesn’t seek medical intervention at all in eir memoir, so I can’t quite grasp why that was the complainant’s immediate concern.

In contrast to the complainant’s apprehension that the queerness in Kobabe’s graphic memoir could be contagious, I think young readers have the right to explore different perspectives and ask themselves difficult questions about their gender and sexuality. Furthermore, it’s important for trans and non-binary readers to encounter experiences similar to their own, as such encounters may help them feel more comfortable in their identities and may help them determine what pronouns are most fitting for their identities. Even Kobabe felt lost as to what pronouns to use until e met another e/em/eir user.

I relied on Kobabe’s graphic memoir in a similar capacity. While some readers may find comfort in the narrative for its genuine interrogation of gender identity, I found solace in Kobabe’s portrayal of discovering eir asexuality. Prior to reading Gender Queer, the only asexual characters I had encountered were Spongebob Squarepants and Todd Chavez from Bojack Horseman, both of whom are essentially grown man-children who draw creativity from their naïve and extroverted personalities. Characters I could relate to and feel distanced from simultaneously. I wanted to see an asexual like myself, someone who is introverted and who logics their way through problems rather than blazing through on instinct alone. Still, as I watched Bojack Horseman with my dad, I grew visibly excited about a character who openly interrogates whether he can date or get married as an asexual, who regularly encounters and debunks stereotypes that assume asexual persons are broken prudes detached from human urges. I grew so excited that my dad had to ask me why, and all I could respond was “This is such a great leap in representation,” as if I were speaking generally as an ally, as if I weren’t asking all the same questions as Todd in my mind. Because there are still too few cases like me in the public eye. My mom is still trying to figure out non-binary identities; how could she ever understand what I am unless there’s more representation?

And then I read Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, and e asked all the same questions I did and experienced all the same anxieties, about dating, about pap smears. Kobabe logics through situations in the way I do and expresses eir creativity similarly through writing and drawing. We both love the fashion of Alexander McQueen and admire figure skater Johnny Weir. We share an inherent fascination with reptiles. Finally, I’ve found a character, a person, with whom I can fully identify, and Wake County cannot take that from me, from others like me who feel alone and lost. Why does every straight woman in the United States have a different icon she can paste to her mood board each day of the week or a romantic heroine she can dream of embodying when she meets Mr. Right, but I hardly have any examples I can point to when I come out to my parents? Why has one writer’s journey to eir queer, asexual identity been deemed obscene, as if my identity is dirty? I’ve abstained, North Carolina; it’s what you told me to do all along. What more do you want?

Natalie Plahuta is in her second year of pursuing her MFA in Creative Nonfiction at George Mason University, where she is the Assistant Nonfiction Editor for the intersectional feminist literary journal So To Speak. She recently graduated with her Bachelor’s in English and a minor in Asian Studies from UNC-Chapel Hill. In 2018, she won the first prize for poetry in the Cynthia DeFord Adams Literary Contest. Although she currently resides in Northern Virginia, Natalie frequently visits her home in Raleigh, North Carolina.

1 thought on “A Wake County Resident’s Perspective on Why It’s Important Not to Ban “Gender Queer””

Great insight!